SEX AMONG BIRDS – A TABOO THAT FLIES RIGHT ABOVE OUR HEADS

In the world of birds, there is a topic that is rarely discussed — if at all.

Not because it doesn’t exist.

But because it feels uncomfortable.

Sex

When we think about birds, we almost always focus on problems: diseases, parasites, deficiencies, treatment, prevention. That matters. It’s necessary. But it’s not their whole life.

Birds are not collections of clinical symptoms with feathers. They are emotional, social beings, capable of forming relationships. And where a relationship exists, intimacy eventually appears.

That is what this article is about.

WHY WE DON’T TALK ABOUT SEX IN BIRDS

Because the word “sex” still creates tension.

Because it is associated with breeding.

Because reproduction gets confused with intimacy.

Because birds are often treated like biological machinery: a breeding pair, eggs, chicks.

But birds do not function like machines.

You cannot force a bird to have sex.

You cannot “set” it to reproduce.

You cannot control it in the way other domesticated animals are controlled.

For a bird to show sexual behavior:

This is not mechanics.

This is emotional biology.

SEX IN BIRDS IS NOT JUST REPRODUCTION

This is one of the biggest myths.

In many bird species, sex:

Sex can be a ritual.

It can be a language.

It can be a confirmation of the relationship.

And yes — sometimes it is also a source of pleasure

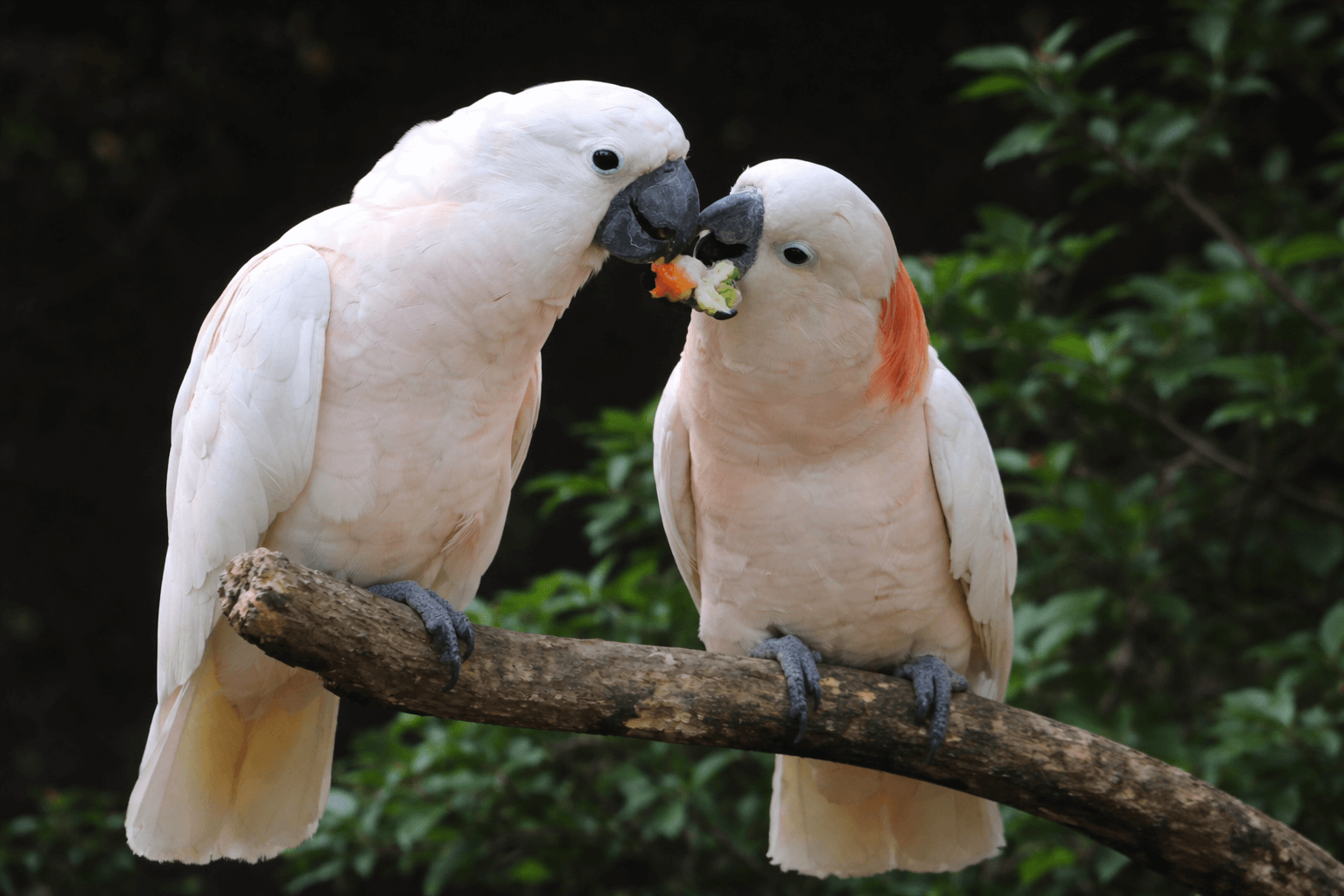

MOLUCCAN COCKATOO – WHEN INTIMACY IS VISIBLE

The Moluccan cockatoo is one of the most striking examples of avian intimacy.

These birds are extremely intelligent, deeply emotional, and strongly bonded to their partners. In their case, sex is not an act separated from the relationship — it is an extension of it.

Sexual behaviors in cockatoos:

WHEN CLOSENESS BECOMES TOO INTENSE

One important clarification must be added: in cockatoos (including Moluccans), closeness can be so intense that it sometimes shifts into behaviors on the edge of dominance, overstimulation, or mutual biting. These birds can genuinely “love touching each other,” but when emotional tension rises, the relationship can become too intense and may result in injuries.

This is not a “pathology.” It is a signal that the level of arousal has crossed a safe boundary. Responsible care therefore requires careful observation of the pair, attention to space, stimuli, routine, and providing other ways to release excess energy. Closeness is natural — but like any intense relationship, it needs wise conditions so it does not turn into something harmful.

NOT JUST COCKATOOS – OTHER EXAMPLES FROM THE AVIAN WORLD

The Moluccan cockatoo is one of the most striking examples of avian intimacy, but it is by no means an exception. Sexual and affiliative behaviors not directly linked to breeding are observed in many other bird species.

In numerous parrots, such as macaws, African grey parrots and amazons, behaviors like prolonged allopreening (mutual feather grooming), partner feeding, and the so-called “cloacal kiss” are commonly observed, including outside the breeding season. In these cases, closeness primarily serves to maintain the bond and regulate the relationship within the pair, rather than to immediately lead to reproduction.

Similar patterns can be seen in strongly monogamous water birds such as swans and geese. In these species, sexual behaviors outside the reproductive period function as rituals that reinforce pair bonds, stabilize relationships and help synchronize partners.

Another well-known example is the albatross. Pairs may spend many years performing complex “dances,” touching beaks and synchronizing body movements long before their first successful breeding attempt. These rituals are not aimed at immediate reproduction, but at building a long-term bond on which future reproductive success depends.

These examples clearly show that sex and intimacy in birds are neither anomalies nor quirks of a single group. They are part of the biology of relationships — tools for communication, emotional regulation and bond strengthening.

IN THE END – WHAT THIS TEXT IS REALLY ABOUT

This text is not an attempt to transfer a human vision of sex onto the world of birds.

It is not about romanticizing their relationships or assigning them human-style intimate scenarios.

That is not the point.

The point is to realize something much simpler — and at the same time much harder to accept: we are not an exception. Sex, closeness, and intimacy did not appear with humans. They existed long before us. They are present in many species, in different forms, serving different functions.

For a long time, we pretended not to see this, because it was easier to believe that only humans “feel things,” while the rest of the living world operates like an automatic system.

And yet sex is here and there. In the quiet of aviaries, in the crowns of trees, in rituals that have nothing to do with our culture — but everything to do with biology, bonding, and safety.

This is not about elevating animals to a human version of sex.

It is about reminding humans that they are not the center of the universe.

It is time to wake up.

Comments