Herida in a bird – what the healing process really looks like and what the so-called granulation tissue is

Many bird keepers believe that if an animal lives in a good, experienced breeding environment, injuries simply do not happen. Unfortunately, this is a myth.

Even under the best conditions, cuts, scratches, and very serious wounds can occur. Why?

Because birds are not only delicate, “pretty” creatures. They are animals with very strong instincts, hormones, and behaviors that cannot be fully controlled, even with extensive experience on the part of the caretaker.

Love, hormones and aggression – when avian logic stops being “human”

The word “love” when applied to birds can be very misleading. From a human perspective, it is associated with care and closeness, but in the avian world hormones and instinct very often take absolute priority.

During the breeding season, behaviors can easily get out of control. This includes dominance, rivalry for a mate and territory, and aggression that can escalate very quickly.

A good example are pheasants of the genus Lophura, birds known for strong intraspecific aggression. Even in large aviaries it may happen that one individual selects a specific victim, attacks are repeated and deliberate, severe injuries occur, and in extreme cases the bird is killed by a companion.

From a human point of view, such logic may be difficult to understand. For the bird, however, it is the result of hormones, hierarchy, and the instinct to survive, without reflection and without the “brakes” humans are familiar with.

Importantly, this does not apply only to species considered aggressive. In parrots, canaries, and other birds as well, courtship may be excessively intense, grabbing a partner by the neck, wing, or leg can lead to wounds, and conflicts can escalate very rapidly. Sometimes, even “out of love,” harm is done.

Most important: an injured bird must be isolated IMMEDIATELY

The first and absolutely fundamental rule with any wound is the immediate isolation of the injured bird.

This is crucial because other birds may continue to attack or peck at the wound, the presence of the flock dramatically increases stress, stress intensifies bleeding and strongly inhibits healing, and a bird after trauma can easily go into shock.

The injured bird should be moved to a safe, quiet place (a transport carrier or hospital cage), provided with warmth, low light, and silence, handled only as much as absolutely necessary, and protected from contact with other birds and excessive human attention. Calm and stress reduction are part of the treatment, not an addition.

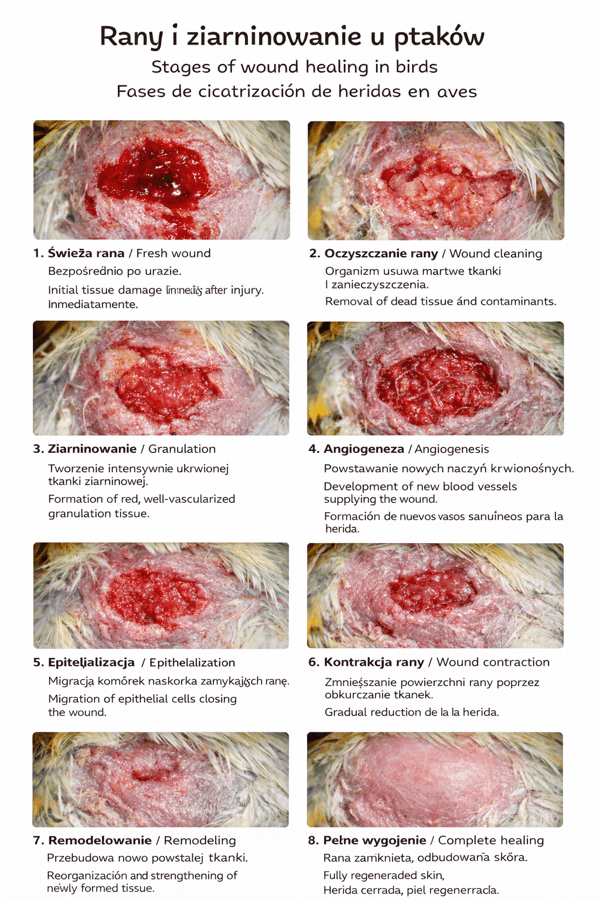

What the wound healing process in a bird looks like – an approximate timeline

Wound healing in birds occurs in stages and rarely looks “nice.” Knowing the approximate time frames helps determine whether the process is progressing correctly.

Days 1–3 – inflammatory phase: the wound is clearly red, may ooze blood or serum, and the tissue is often swollen and sensitive. At this stage there is no granulation tissue yet, and that is normal.

Around days 3–5 – beginning of granulation: new pink to red tissue appears, the wound looks wetter and more “fleshy,” and it may bleed easily when touched. This stage often causes panic, even though it marks the start of proper healing.

Days 5–10 – active granulation: granulation tissue visibly fills the defect, the surface may appear uneven and moist, and the wound edges gradually begin to come together. This is a critical phase—drying the wound, tearing tissue, or aggressive disinfection can set healing back by many days or even weeks.

Around days 10–14 – epithelialization: a new skin layer begins to form, the wound gradually closes, and in the following weeks feathers may regrow if the follicles were not permanently damaged.

What a bird keeper’s first aid kit should contain

Every bird breeder or keeper should have a prepared first aid kit. Not to treat on their own, but to provide first aid and protect the wound until veterinary consultation.

A basic kit should include sterile gauze pads and compresses in various sizes, self-adhering elastic bandage without adhesive, saline solution, an alcohol-free disinfectant safe for birds, disposable gloves, small scissors and tweezers, a towel or soft cloth for gentle restraint, a hospital cage or transport carrier, and contact information for an avian veterinarian.

The kit is not meant to “treat everything.” Its purpose is protection, stabilization, and buying time.

First aid – the limits of a caretaker’s responsibility

The caretaker’s role is to stop bleeding with gentle pressure using sterile gauze, clean the wound with saline solution without scrubbing, gently disinfect with a bird-safe product, protect the wound if possible, provide calm, warmth, and silence, and contact a veterinarian.

The caretaker does not treat wounds in birds.

In more serious injuries, pain medication is often required, birds mask pain very well, antibiotic therapy is frequently necessary, and sometimes systemic treatment is required. In deep and extensive wounds, antibiotics are often essential because a local infection can quickly develop into a generalized infection that poses a real threat to life. Therefore, contacting a veterinarian is not an option—it is a necessity.

Severe and deep wounds – an emergency situation

If the wound is extensive, deep, involves the head or neck, or looks dramatic, there is no time to wait.

The caretaker’s role is limited to stopping bleeding, gentle cleaning, covering with a sterile dressing, providing warmth and calm, and immediate transport to a veterinarian.

It is not allowed to remove tissue, “clean down to the bone,” use aggressive preparations, or administer medications without professional guidance.

Common myths about wounds in birds

“Red tissue means infection” – very often it is healthy granulation tissue.

“The wound must be dried” – drying slows healing and promotes tissue death.

“The red tissue must be removed” – removing granulation tissue sets healing back.

Important information: I am not a veterinarian. This article is based on experience, observation, and work with birds. It describes a case; each case is a different story. It does not replace veterinary advice.

Comments